- Home

- Kurt Vonnegut

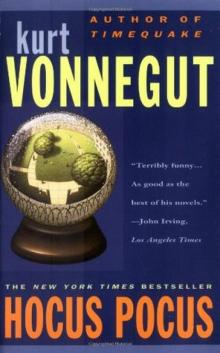

Hocus Pocus Page 11

Hocus Pocus Read online

Page 11

He was talking about the sign that said "THE COMPLICATED FUTILITY OF IGNORANCE."

"All I knew was that I didn't want my daughter or anybody's child to see a message that negative every time she comes into the library," he said. "And then I found out it was you who was responsible for it."

"What's so negative about it?" I said.

"What could be a more negative word than 'futility'?" he said.

" 'Ignorance,' " I said.

"There you are," he said. I had somehow won his argument for him.

"I don't understand," I said.

"Precisely," he said. "You obviously do not understand how easily discouraged the typical Tarkington student is, how sensitive to suggestions that he or she should quit trying to be smart. That's what the word 'futile' means: 'Quit, quit, quit.' "

"And what does 'ignorance' mean?" I said.

"If you put it up on the wall and give it the prominence you have," he said, "it's a nasty echo of what so many Tarkingtonians were hearing before they got here: 'You're dumb, you're dumb, you're dumb.' And of course they aren't dumb."

"I never said they were," I protested.

"You reinforce their low self-esteem without realizing what you are doing," he said. "You also upset them with humor appropriate to a barracks, but certainly not to an institution of higher learning."

"You mean about Yen and fellatio?" I said. "I would never have said it if I'd thought a student could hear me."

"I am talking about the entrance hall of the library again," he said.

"I can't think of what else is in there that might have offended you," I said.

"It wasn't I who was offended," he said. "It was my daughter."

"I give up," I said. I wasn't being impudent. I was abject.

"On the same day Kimberley heard you talk about Yen and fellatio, before classes had even begun," he said, "a senior led her and the other freshmen to the library and solemnly told them that the bell clappers on the wall were petrified penises. That was surely barracks humor the senior had picked up from you."

For once I didn't have to defend myself. Several of the Trustees assured Wilder that telling freshmen that the clappers were penises was a tradition that antedated my arrival on campus by at least 20 years.

But that was the only time they defended me, although 1 of them had been my student, Madelaine Astor, nee Peabody, and 5 of them were parents of those I had taught. Madelaine dictated a letter to me afterward, explaining that Jason Wilder had promised to denounce the college in his column and on his TV show if the Trustees did not fire me.

So they dared not come to my assistance.

SHE SAID, TOO, that since she, like Wilder, was a Roman Catholic, she was shocked to hear me say on tape that Hitler was a Roman Catholic, and that the Nazis painted crosses on their tanks and airplanes because they considered themselves a Christian army. Wilder had played that tape right after I had been cleared of all responsibility for freshmen's being told that the clappers were penises.

Once again I was in deep trouble for merely repeating what somebody else had said. It wasn't something my grandfather had said this time, or somebody else who couldn't be hurt by the Trustees, like Paul Slazinger. It was something my best friend Damon Stern had said in a History class only a couple of months before.

If Jason Wilder thought I was an unteacher, he should have heard Damon Stern! Then again, Stern never told the awful truth about supposedly noble human actions in recent times. Everything he debunked had to have transpired before 1950, say.

So I happened to sit in on a class where he talked about Hitler's being a devout Roman Catholic. He said something I hadn't realized before, something I have since discovered most Christians don't want to hear: that the Nazi swastika was intended to be a version of a Christian cross, a cross made out of axes. Stern said that Christians had gone to a lot of trouble denying that the swastika was just another cross, saying it was a primitive symbol from the primordial ooze of the pagan past.

And the Nazis' most valuable military decoration was the Iron Cross.

And the Nazis painted regular crosses on all their tanks and airplanes.

I came out of that class looking sort of dazed, I guess. Who should I run into but Kimberley Wilder?

"What did he say today?" she said.

"Hitler was a Christian," I said. "The swastika was a Christian cross."

She got it on tape.

I DIDN'T RAT on Damon Stern to the Trustees. Tarkington wasn't West Point, where it was an honor to squeal.

MADELAINE AGREED WITH Wilder, too, she said in her letter, that I should not have told my Physics students that the Russians, not the Americans, were the first to make a hydrogen bomb that was portable enough to be used as a weapon. "Even if it's true," she wrote, "which I don't believe, you had no business telling them that."

She said, moreover, that perpetual motion was possible, if only scientists would work harder on it.

She had certainly backslid intellectually since passing her orals for her Associate in the Arts and Sciences Degree.

I USED TO tell classes that anybody who believed in the possibility of perpetual motion should be boiled alive like a lobster.

I was also a stickler about the Metric System. I was famous for turning my back on students who mentioned feet or pounds or miles to me.

They hated that.

I DIDN'T DARE teach like that in the prison across the lake, of course.

Then again, most of the convicts had been in the drug business, and were either Third World people or dealt with Third World people. So the Metric System was old stuff to them.

RATHER THAN RAT on Damon Stern about the Nazis' being Christians, I told the Trustees that I had heard it on National Public Radio. I said I was very sorry about having passed it on to a student. "I feel like biting off my tongue," I said.

"What does Hitler have to do with either Physics or Music Appreciation?" said Wilder.

I might have replied that Hitler probably didn't know any more about physics than the Board of Trustees, but that he loved music. Every time a concert hall was bombed, I heard somewhere, he had it rebuilt immediately as a matter of top priority. I think I may actually have learned that from National Public Radio.

I said instead, "If I'd known I upset Kimberley as much as you say I did, I would certainly have apologized. I had no idea, sir. She gave no sign."

WHAT MADE ME weak was the realization that I had been mistaken to think that I was with family there in the Board Room, that all Tarkingtonians and their parents and guardians had come to regard me as an uncle. My goodness--the family secrets I had learned over the years and kept to myself! My lips were sealed. What a faithful old retainer I was! But that was all I was to the Trustees, and probably to the students, too.

I wasn't an uncle. I was a member of the Servant Class.

They were letting me go.

Soldiers are discharged. People in the workplace are fired. Servants are let go.

"Am I being fired?" I asked the Chairman of the Board incredulously.

"I'm sorry, Gene," he said, "but we're going to have to let you go."

THE PRESIDENT OF the college, Tex Johnson, sitting two chairs away from me, hadn't let out a peep. He looked sick. I surmised mistakenly that he had been scolded for having let me stay on the faculty long enough to get tenure. He was sick about something more personal, which still had a lot to do with Professor Eugene Debs Hartke.

He had been brought in as President from Rollins College down in Winter Park, Florida, where he had been Provost, after Sam Wakefield did the big trick of suicide. Henry "Tex" Johnson held a Bachelor's Degree in Business Administration from Texas Tech in Lubbock, and claimed to be a descendant of a man who had died in the Alamo. Damon Stern, who was always turning up little-known facts of history, told me, incidentally, that the Battle of the Alamo was about slavery. The brave men who died there wanted to secede from Mexico because it was against the law to own slaves in Mexico. They were figh

ting for the right to own slaves.

Since Tex's wife and I had been lovers, I knew that his ancestors weren't Texans, but Lithuanians. His father, whose name certainly wasn't Johnson, was a Lithuanian second mate on a Russian freighter who jumped ship when it put in for emergency repairs at Corpus Christi. Zuzu told me that Tex's father was not only an illegal immigrant but the nephew of the former Communist boss of Lithuania.

So much for the Alamo.

I TURNED TO him at the Board meeting, and I said, "Tex--for pity sakes, say something! You know darn good and well I'm the best teacher you've got! I don't say that. The students do! Is the whole faculty going to be brought before this Board, or am I the only one? Tex?"

He stared straight ahead. He seemed to have turned to cement. "Tex?" Some leadership!

I put the same question to the Chairman, who had been pauperized by Microsecond Arbitrage but didn't know it yet. "Bob--" I began.

He winced.

I began again, having gotten the message in spades that I was a servant and not a relative: "Mr. Moellenkamp, sir--" I said, "you know darn well, and so does everybody else here, that you can follow the most patriotic, deeply religious American who ever lived with a tape recorder for a year, and then prove that he's a worse traitor than Benedict Arnold, and a worshipper of the Devil. Who doesn't say things in a moment of passion or absentmindedness that he doesn't wish he could take back? So I ask again, am I the only one this was done to, and if so, why?"

He froze.

"Madelaine?" I said to Madelaine Astor, who would later write me such a dumb letter.

She said she did not like it that I had told students that a new Ice Age was on its way, even if I had read it in The New York Times. That was another thing I'd said that Wilder had on tape. At least it had something to do with science, and at least it wasn't something I had picked up from Slazinger or Grandfather Wills or Damon Stern. At least it was the real me.

"The students here have enough to worry about," she said. "I know I did."

She went on to say that there had always been people who had tried to become famous by saying that the World was going to end, but the World hadn't ended.

There were nods of agreement all around the table. I don't think there was a soul there who knew anything about science.

"When I was here you were predicting the end of the World," she said, "only it was atomic waste and acid rain that were going to kill us. But here we are. I feel fine. Doesn't everybody else feel fine? So pooh."

She shrugged. "About the rest of it," she said, "I'm sorry I heard about it. It made me sick. If we have to go over it again, I think I'll just leave the room."

Heavens to Betsy! What could she have meant by "the rest of it"? What could it be that they had gone over once, and were going to have to go over again with me there? Hadn't I already heard the worst?

No.

16

"THE REST OF it" was in a manila folder in front of Jason Wilder. So there is Manila playing a big part in my life again. No Sweet Rob Roys on the Rocks this time.

In the folder was a report by a private detective hired by Wilder to investigate my sex life. It covered only the second semester, and so missed the episode in the sculpture studio. The gumshoe recorded 3 of 7 subsequent trysts with the Artist in Residence, 2 with a woman from a jewelry company taking orders for class rings, and maybe 30 with Zuzu Johnson, the wife of the President. He didn't miss a thing Zuzu and I did during the second semester. There was only 1 misunderstood incident: when I went up into the loft of the stable, where the Lutz Carillon had been stored before there was a tower and where Tex Johnson was crucified 2 years ago. I went up with the aunt of a student. She was an architect who wanted to see the pegged post-and-beam joinery up there. The operative assumed we made love up there. We hadn't.

We made love much later that afternoon, in a toolshed by the stable, in the shadow of Musket Mountain when the Sun goes down.

I WASN'T TO see the contents of Wilder's folder for another 10 minutes or so. Wilder and a couple of others wanted to go on discussing what really bothered them about me, which was what I had been doing, supposedly, to the students' minds. My sexual promiscuity among older women wasn't of much interest to them, the College President excepted, save as a handy something for which I could be fired without raising the gummy question of whether or not my rights under the First Amendment of the Constitution had been violated.

Adultery was the bullet they would put in my brain, so to speak, after I had been turned to Swiss cheese by the firing squad.

TO TEX JOHNSON, the closet Lithuanian, the contents of the folder were more than a gadget for diddling me out of tenure. They were a worse humiliation for Tex than they were for me.

At least they said that my love affair with his wife was over.

He stood up. He asked to be excused. He said that he would just as soon not be present when the Trustees went over for the second time what Madelaine had called "the rest of it."

He was excused, and was apparently about to leave without saying anything. But then, with one hand on the doorknob, he uttered two words chokingly, which were the title of a novel by Gustave Flaubert. It was about a wife who was bored with her husband, who had an exceedingly silly love affair and then committed suicide.

"Madame Bovary," he said. And then he was gone.

HE WAS A cuckold in the present, and crucifixion awaited him in the future. I wonder if his father would have jumped ship in Corpus Christi if he had known what an unhappy end his only son would come to under American Free Enterprise.

I HAD READ Madame Bovary at West Point. All cadets in my day had to read it, so that we could demonstrate to cultivated people that we, too, were cultivated, should we ever face that challenge. Jack Patton and I read it at the same time for the same class. I asked him afterward what he thought of it. Predictably, he said he had to laugh like hell.

He said the same thing about Othello and Hamlet and Romeo and Juliet.

I CONFESS THAT to this day I have come to no firm conclusions about how smart or dumb Jack Patton really was. This leaves me in doubt about the meaning of a birthday present he sent me in Vietnam shortly before the sniper killed him with a beautiful shot in Hue, pronounced "whay." It was a gift-wrapped copy of a stroke magazine called Black Garterbelt. But did he send it to me for its pictures of women naked except for black garterbelts, or for a remarkable science fiction story in there, "The Protocols of the Elders of Tralfamadore"?

But more about that later.

I HAVE NO idea how many of the Trustees had read Madame Bovary. Two of them would have had to have it read aloud to them. So I was not alone in wondering why Tex Johnson would have said, his hand on the doorknob, "Madame Bovary."

If I had been Tex, I think I might have gotten off the campus as fast as possible, and maybe drowned my sorrows among the nonacademics at the Black Cat Cafe. That was where I was going to wind up that afternoon. It would have been funny in retrospect if we had wound up as a couple of sloshed buddies at the Black Cat Cafe.

IMAGINE MY SAYING to him or his saying to me, both of us drunk as skunks, "I love you, you old son of a gun. Do you know that?"

ONE TRUSTEE HAD it in for me on personal grounds. That was Sydney Stone, who was said to have amassed a fortune of more than $1,000,000,000 in 10 short years, mainly in commissions for arranging sales of American properties to foreigners. His masterpiece, maybe, was the transfer of ownership of my father's former employer, E. I. Du Pont de Nemours & Company, to I. G. Farben in Germany.

"There is much I could probably forgive, if somebody put a gun to my head, Professor Hartke," he said, "but not what you did to my son." He himself was no Tarkingtonian. He was a graduate of the Harvard Business School and the London School of Economics.

"Fred?" I said.

"In case you haven't noticed," he said, "I have only 1 son in Tarkington. I have only 1 son anywhere." Presumably this 1 son, without having to lift a finger, would himself 1 day have $1,000,000,000.

"What did I do to Fred?" I said.

"You know what you did to Fred," he said.

What I had done to Fred was catch him stealing a Tarkington beer mug from the college bookstore. What Fred Stone did was beyond mere stealing. He took the beer mug off the shelf, drank make-believe toasts to me and the cashier, who were the only other people there, and then walked out.

I had just come from a faculty meeting where the campus theft problem had been discussed for the umpteenth time. The manager of the bookstore told us that only one comparable institution had a higher percentage of its merchandise stolen than his, which was the Harvard Coop in Cambridge.

So I followed Fred Stone out to the Quadrangle. He was headed for his Kawasaki motorcycle in the student parking lot. I came up behind him and said quietly, with all possible polite-ness, "I think you should put that beer mug back where you got it, Fred. Either that or pay for it."

"Oh, yeah?" he said. "Is that what you think?" Then he smashed the mug to smithereens on the rim of the Vonnegut Memorial Fountain. "If that's what you think," he said, "then you're the one who should put it back."

I reported the incident to Tex Johnson, who told me to forget it.

But I was mad. So I wrote a letter about it to the boy's father, but never got an answer until the Board meeting.

"I can never forgive you for accusing my son of theft," the father said. He quoted Shakespeare on behalf of Fred. I was supposed to imagine Fred's saying it to me.

" 'Who steals my purse steals trash; 'tis something, nothing,' " he said. " ''Twas mine, 'tis his, and has been slave to thousands,' " he went on, " 'but he that filches from me my good name robs me of that which not enriches him and makes me poor indeed.' "

"If I was wrong, sir, I apologize," I said.

"Too late," he said.

17

THERE WAS 1 Trustee I was sure was my friend. He would have found what I said on tape funny and interesting. But he wasn't there. His name was Ed Bergeron, and we had had a lot of good talks about the deterioration of the environment and the abuses of trust in the stock market and the banking industry and so on. He could top me for pessimism any day.

Slaughterhouse-Five

Slaughterhouse-Five Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction

Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian Breakfast of Champions

Breakfast of Champions While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction

While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction Slapstick or Lonesome No More!

Slapstick or Lonesome No More! Cat's Cradle

Cat's Cradle The Sirens of Titan

The Sirens of Titan A Man Without a Country

A Man Without a Country Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction

Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction Bluebeard

Bluebeard Hocus Pocus

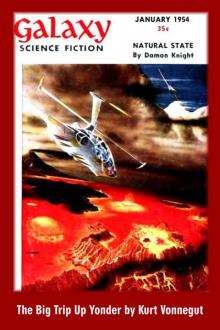

Hocus Pocus The Big Trip Up Yonder

The Big Trip Up Yonder Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage

Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage Jailbird

Jailbird Happy Birthday, Wanda June

Happy Birthday, Wanda June Welcome to the Monkey House

Welcome to the Monkey House Player Piano

Player Piano Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage Love, Kurt

Love, Kurt Timequake

Timequake God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater 2 B R 0 2 B

2 B R 0 2 B The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity

The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity Mother Night

Mother Night Deadeye Dick

Deadeye Dick Galápagos

Galápagos Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday We Are What We Pretend to Be

We Are What We Pretend to Be Look at the Birdie

Look at the Birdie Basic Training

Basic Training Armageddon in Retrospect

Armageddon in Retrospect Basic Training (Kindle Single)

Basic Training (Kindle Single) If This Isn't Nice, What Is?

If This Isn't Nice, What Is? Bagombo Snuff Box

Bagombo Snuff Box The Petrified Ants

The Petrified Ants Cat's Cradle: A Novel

Cat's Cradle: A Novel Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)