- Home

- Kurt Vonnegut

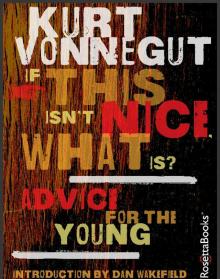

If This Isn't Nice, What Is?

If This Isn't Nice, What Is? Read online

If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?

Advice for the Young

Kurt Vonnegut

Introduction by Dan Wakefield

Copyright

If This Isn’t Nice, What Is?

Copyright © 2013 by Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Copyright Trust

Cover art to the electronic edition copyright © 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Electronic edition published 2013 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York.

Cover jacket design by Misha Beletsky.

ISBN ePub edition: 9780795333637

Contents

INTRODUCTION

BACCALAUREATE

HOW TO MAKE MONEY AND FIND LOVE!

VONNEGUT GIVES ADVICE TO GRADUATING WOMEN (WHICH ALL MEN SHOULD KNOW ABOUT!)

HOW TO HAVE SOMETHING MOST BILLIONAIRES DON’T HAVE

WHY YOU CAN’T STOP ME FROM SPEAKING ILL OF THOMAS JEFFERSON

HOW MUSIC CURES OUR ILLS (AND THERE ARE LOTS OF THEM)

DON’T DESPAIR IF YOU NEVER WENT TO COLLEGE!

WHAT THE “GHOST DANCE” OF THE NATIVE AMERICANS AND THE CUBIST MOVEMENT OF FRENCH PAINTERS HAD IN COMMON

HOW VONNEGUT LEARNED FROM A TEACHER “WHAT ARTISTS DO”

DON’T FORGET WHERE YOU COME FROM

VONNEGUT UNSTUCK—QUOTES TO PONDER

Do you have a favorite Kurt Vonnegut quote? Join in on the discussion and share your thoughts with other Vonnegut fans at www.mywejit.com/#!vonnegut.

INTRODUCTION

After the publication of his novel Slaughterhouse-Five brought him worldwide acclaim in 1969, Kurt Vonnegut became one of America’s most popular graduation speakers. Even before that first of many best-sellers was published, Vonnegut had become an underground hero of the youth of the sixties who were hungry for new ways of looking at the world and alternatives to the status quo. College students were passing around dog-eared paperback copies of his earlier novels, such as Cat’s Cradle and The Sirens of Titan, even before Slaughterhouse-Five had made him a household name. From his earliest short stories that were published in the popular weeklies of the nineteen-fifties, including Colliers and The Saturday Evening Post, Vonnegut’s work spoke to young people, and that appeal has never faded. His novels, essays, and stories are taught in colleges and high schools throughout the U.S., and as Prof. Shaun O’Connell of the University of Massachusetts at Boston has told me, “It’s hard to get students to read Updike and Bellow any more, but they still love Vonnegut.”

To his surprise and chagrin, Vonnegut was hailed as a “spokesman” of youth and a hero of the counterculture of the sixties, yet he was, ironically, a “counter-counterculture” figure. He satirized the easy promises to inner and world peace being peddled by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in an article for Esquire called “Yes, We Have No Nirvanas.” As Eastern meditations such as Zen became a fad, Vonnegut maintained that we had our own Western method of achieving the same results of slowing the heartbeat and stilling the mind; it was called “reading short stories.” He called this practice “Buddhist Catnaps.” He was not, however, one of those adults of the era who found nothing to admire in the youth culture. He had written that “The function of the artist is to make people like life better than before,” and when asked if he’d ever seen that done he answered, “Yes, the Beatles did it.”

He also loved the blues, and jazz. He wrote to a friendly literary critic that, “During my childhood in Indianapolis, local jazz musicians excited me and made me happy.”

He did not believe drugs had such an effect. In one speech in this collection, he tells his audience: “I’ve been a coward about heroin and cocaine and LSD and so on…. I did smoke a joint of marijuana one time with Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead, just to be sociable. It didn’t seem to do anything to me, one way or the other, so I never did it again.”

Hardly the words of a hippie. One of the well-known hippies of that era, the writer Raymond Mungo, invited me and Vonnegut to visit the commune he started in Brattleboro, Vermont (and later wrote about in his memoir Total Loss Farm). He told us that one reason he and his friends wanted to start the commune and learn to “live off the land” in a simple way was that “we want to be the last people on earth.” Vonnegut said, “Isn’t that kind of a stuck-up kind of thing to want to be?”

In the way he spoke and the way he wrote, Vonnegut was always coming up with the plain-spoken words and phrases that people thought but didn’t say, the ideas that expressed inner feelings, that rattled preconceptions and made you look at things from a different angle. He was the one who pointed out “the elephant in the room,” the one who saw that the Emperor had no clothes.

That same Raymond Mungo who ushered me and Vonnegut around his commune in 1970 emailed me recently after reading a book of Vonnegut’s Letters that “Kurt was and remains an important writer and one who will be read beyond all our lifetimes.” A new generation of Vonnegut fans was introduced to his work in 2005 when he appeared on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart with his last book, A Man Without a Country, and teenagers are still moved today by his stories such as Harrison Bergeron that are taught in high school classes.

Vonnegut neither “wrote down” to his readers nor tried to go over their heads with wisdom. He was playful at the same time he was profound, and in that same style and spirit he spoke to graduating classes. He did not speak to them as if they were a different, lesser breed because they were young; he disdained “generation generalizations.” He told one of these graduating classes “…we are not members of different generations, as unlike, as some people would have us believe, as Eskimos and Australian Aborigines. We are all so close to each other in time that we should think of ourselves as brothers and sisters. … Whenever my children complain about the planet to me, I say ‘Shut up! I just got here myself.’” (Vonnegut had three children of his own, and adopted four others.)

Popular as he was as a graduation speaker, Vonnegut never graduated from college. He left Cornell to join the Army in World War II, and the Army sent him to study bacteriology at Butler University and mechanical engineering at Carnegie Tech and the University of Tennessee, then assigned him to the infantry and gave him a rifle. While serving as an advanced scout for the 106th Infantry in the Battle of the Bulge, he was captured by the Germans and sent to a prisoner of war Camp in Dresden, where he survived the firebombing of that city while quartered in an underground meat locker called Slaughterhouse-Five. When he came home from the war he studied anthropology at the University of Chicago on the G.I. Bill and worked as a reporter for the Chicago News Bureau. Although he completed all the course work for his master’s degree, his ideas for a thesis were turned down, and he had to move on to take a job in public relations at General Electric. He was given an honorary degree by the university years later, after he was famous.

“So it goes…”

Vonnegut’s fame as a writer did not come until he was 47 years old. Before that he struggled to support a large family—not only his wife and their own three children, but three children of his sister who died of cancer at age 41, a day after her husband had been killed when his commuter train crashed off a bridge. The popular weekly magazines of the fifties, whose payments for his short stories enabled Vonnegut to leave his job at General Electric, died off with the advent of television, and he had to scramble to make a living. He failed to sell a shirt company on his idea for a new kind of bow tie, had no success creating a new board game, opened a dealership for Saab automobil

es when they were as yet little known in this country, and when that failed, commuted to Boston to write for an ad agency; he was turned down for a job teaching English at Cape Cod Community College, taught at a school for troubled boys, was turned down for a Guggenheim Fellowship, and through it all, kept writing. He died, in 2007, at the age of 84, still writing.

He was not about to peddle cut-rate formulas for overnight success or blue-sky bromides to young people who sought his advice.

Unlike most graduation speakers, who have a “canned” speech for all such occasions, simply inserting the name of a new university, Vonnegut brought something freshly minted, coming up with new ideas, new stories, new sources of wit and provocations to think. He did, however, have certain cherished themes that he managed to work in to almost all his talks—the appreciation of teachers, the importance of noticing and acknowledging the small, sweet moments of everyday life by stopping to say, as his Uncle Alex had taught him, “If this isn’t nice, what is?” His messages to graduates were not all sweetness and light by a long shot. There is always his despair at the destruction of the planet, his contempt for the politicians who get us into war from the safety of their age and position, our need for the extended families and puberty ceremonies that gave strength to past societies and whose absence plagues our own.

Vonnegut wrote that “A writer is first and foremost a teacher,” and his talks to graduates always taught the lesson that underlies all his work, a lesson, bluntly uttered by a character in one of his early novels, that he passed on to fans who sought his advice: “There’s only one rule I know of—Goddam it, you’ve got to be kind.” Coming from a long line of German Freethinkers, Vonnegut was not a Christian, though he spoke of Jesus as “the greatest and most humane of human beings.” In a talk he gave to St. Clement Episcopal Church in New York City (“Palm Sunday”), he said: “I am enchanted by the Sermon on the Mount. Being merciful, it seems to me, is the only good idea we have had so far. Perhaps we will get another good idea by and by—and then we will have two good ideas.”

He served as honorary chairman of the American Humanist Society, and explained in one of his talks that “We Humanists behave as honorably as we can without any expectations of rewards or punishments in the afterlife. We serve as best we can the only abstraction with which we have any familiarity, which is our community.”

Vonnegut was a staunch believer in serving one’s community, wherever or whatever it might be. Although some graduating classes will have a “handful of celebrities” who move on to the national stage, he pointed out that most would find themselves “building or strengthening your communities. Please love that destiny, if it turns out to be yours—for communities are all that’s substantial about the world. The rest is hoop-la. And for your footloose generation, that community could as easily be New York City or Washington, Paris or Houston—or Adelaide, Australia. Or Shanghai or Kuala Lumpur.”

Or it might be the city or town where you were born and grew up. Vonnegut and I were both born and grew up in Indianapolis, but left to go off to college and live far away from there. Once while we were walking down the street in New York, Vonnegut turned to me and said, “You know, Dan, we never had to leave home to be writers, because there are people there just as smart and just as dumb, just as kind and just as mean, as anywhere else in the world.” He was proud of the education he received at Shortridge High School, where he had worked on our school paper, The Daily Echo, as I did a decade later. When asked once by an interviewer “Where did you get your radical ideas?” he answered proudly and without hesitation, “The public schools of Indianapolis.”

Vonnegut took part in the communities he lived in, serving in the Volunteer Fire Department of Alplaus, New York, where he lived while working for General Electric in Schenectady. When he lived in Barnstable, on Cape Cod, Kurt and his wife Jane conducted a Great Books course for the community. (A Phi Beta Kappa from Swarthmore, Jane had him read The Brothers Karamazov on their honeymoon.) When he moved to New York City, he became deeply involved in the PEN Club, serving as vice president and fighting for the rights of writers around the world.

If your destiny was not to live and work in a big city or a foreign land, it was just as important and admirable, in Vonnegut’s view, to serve the place where you found yourself and felt yourself fulfilled, no matter how small or obscure that place might seem to the rest of the world. When his friend Jerome Klinkowitz, a teacher and literary critic, asked his advice about moving from a small town in Iowa to a more prestigious position on the East Coast, Vonnegut wrote him “I am certain you are highly valued and badly needed right where you are. That must be a nourishing situation. If you move East, you may find that life becomes a lot less personal.” Klinkowitz heeded his advice to stay where he was, and told me years later, “It was the best advice I ever got.”

In his talks, as in his books and stories and essays, Vonnegut conveys what he feels is the message many people “need desperately to receive”:

“I feel and think much as you do, care about many of the things you care about, although most people don’t care about them. You are not alone.”

While most of the talks here are to graduating classes, one is to the Indiana Civil Liberties Union, and another is an acceptance of the Carl Sandburg Literary Award; what he has to say in both is as relevant to young people as his words to the graduates. They convey the message that he sent to the chairman of the Drake School Board of Drake, North Dakota, who had not only banned his novel Slaughterhouse-Five, but for good measure, had burned copies of it in the high school furnace:

“…if you were to bother to read my books, to behave as educated persons would, you would learn that they are not sexy, and do not argue in favor of wildness of any kind. They beg that people be kinder and more responsible than they often are. It is true that some of the characters speak coarsely. That is because people speak coarsely in real life. Especially soldiers and hard-working men speak coarsely, and even our most sheltered children know that. And we all know, too, that those words really don’t damage children much. They didn’t damage us when we were young. It was evil deeds and lying that hurt us.”

You will find no lies in Vonnegut’s words of advice. He is one of the truth tellers of our time.

— Dan Wakefield

BACCALAUREATE

A show of hands, please:

How many of you have had a teacher

at any stage of your education,

from the first grade until this day in May,

who made you happier to be alive,

prouder to be alive,

than you had previously believed

possible?

Good!

Now say the name of that teacher

to someone

sitting or standing near you.

All done?

Thank you, and drive home safely,

and God bless you all.

HOW TO MAKE MONEY AND FIND LOVE!

As if that information weren’t enough. Vonnegut explains why we laugh at jokes, why we are lonely, and why there are really six seasons in the year instead of only four.1

Your class spokesperson has just said that she is sick and tired of hearing people say, “I’m glad I’m not a young person these days.” All I can say is, “I’m glad I’m not a young person these days.”

Your college’s president wished to exclude all negative thinking from his farewell to you, and so has asked me to make this announcement: “All persons who still owe parking fees are to pay up before leaving the property, or there will be monkey business with their transcripts.”

When I was a boy in Indianapolis, there was a humorist there named Kin Hubbard. He wrote a few lines for The Indianapolis News every day. Indianapolis needs all the humorists it can get. He was often as witty as Oscar Wilde. He said, for instance, that prohibition was better than no liquor at all. He said that whoever named near-beer was a poor judge of distance.

I assume that the really important stuf

f has been spread out over your four years here and that you have no need of anything much from me. This is lucky for me. I have only this to say, basically: This is the end—this is childhood’s end for certain. “Sorry about that,” as they used to say in the Vietnam War.

Perhaps you have read the novel Childhood’s End by Arthur C. Clarke, one of the few masterpieces in the field of science fiction. All of the others were written by me. In Clarke’s novel, one of the characters undergoes a spectacular evolutionary change. The children become very different from the parents, less physical, more spiritual—and one day they form up into a sort of column of light which spirals out into the universe, its mission unknown. The book ends there. You seniors, however, look a great deal like your parents, and I doubt that you will go radiantly into space as soon as you have your diplomas in hand. It is far more likely that you will go to Buffalo or Rochester or East Quogue—or Cohoes.

And I suppose you will all want money and true love, among other things. I will tell you how to make money: Work very hard. I will tell you how to win love: Wear nice clothing and smile all the time. Learn the words to all the latest songs.

What other advice can I give you? Eat lots of bran to provide necessary bulk in your diet. The only advice my father ever gave me was this: “Never stick anything in your ear.” The tiniest bones in your body are inside your ears, you know—and your sense of balance, too. If you mess around with your ears, you could not only become deaf, but you could also start falling down all the time. So just leave your ears completely alone. They’re fine, just the way they are.

Don’t murder anybody—even though New York State does not use the death penalty.

That’s about it.

One sort of optional thing you might do is to realize there are six seasons instead of four. The poetry of four seasons is all wrong for this part of the planet, and this may explain why we are so depressed so much of the time. I mean, Spring doesn’t feel like Spring a lot of the time, and November is all wrong for Fall and so on. Here is the truth about the seasons: Spring is May and June! What could be springier than May and June? Summer is July and August. Really hot, right? Autumn is September and October. See the pumpkins? Smell those burning leaves. Next comes the season called “Locking.” That is when Nature shuts everything down. November and December aren’t Winter. They’re Locking. Next comes Winter, January and February. Boy! Are they ever cold! What comes next? Not Spring. Unlocking comes next. What else could April be?

Slaughterhouse-Five

Slaughterhouse-Five Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction

Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian Breakfast of Champions

Breakfast of Champions While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction

While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction Slapstick or Lonesome No More!

Slapstick or Lonesome No More! Cat's Cradle

Cat's Cradle The Sirens of Titan

The Sirens of Titan A Man Without a Country

A Man Without a Country Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction

Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction Bluebeard

Bluebeard Hocus Pocus

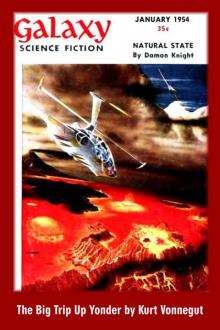

Hocus Pocus The Big Trip Up Yonder

The Big Trip Up Yonder Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage

Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage Jailbird

Jailbird Happy Birthday, Wanda June

Happy Birthday, Wanda June Welcome to the Monkey House

Welcome to the Monkey House Player Piano

Player Piano Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage Love, Kurt

Love, Kurt Timequake

Timequake God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater 2 B R 0 2 B

2 B R 0 2 B The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity

The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity Mother Night

Mother Night Deadeye Dick

Deadeye Dick Galápagos

Galápagos Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday We Are What We Pretend to Be

We Are What We Pretend to Be Look at the Birdie

Look at the Birdie Basic Training

Basic Training Armageddon in Retrospect

Armageddon in Retrospect Basic Training (Kindle Single)

Basic Training (Kindle Single) If This Isn't Nice, What Is?

If This Isn't Nice, What Is? Bagombo Snuff Box

Bagombo Snuff Box The Petrified Ants

The Petrified Ants Cat's Cradle: A Novel

Cat's Cradle: A Novel Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)