- Home

- Kurt Vonnegut

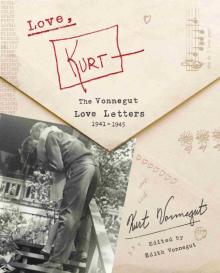

Love, Kurt

Love, Kurt Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Kurt Vonnegut LLC

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Hardback ISBN 9780593133019

Ebook ISBN 9780593133026

randomhousebooks.com

Book design by Barbara M. Bachman, adapted for ebook

Cover design: Ella Laytham

Cover images: courtesy of Edith Vonnegut (type, drawings, photographs); © Triff/Shutterstock (envelope)

rhid_prh_5.6.0_c0_r0

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Pre-1941: Two Indianapolis Families

1941: First Love

1942: Junior Year

1943: War at Home

1944: Shipping Out

1945: Dresden Firebombing and Coming Home

1945: Back Home

Love, Woofy

Beyond 1945

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Introduction

by Edith Vonnegut

I found these letters written from my father, Kurt Vonnegut, to my mother, Jane Marie Cox, deep under the eaves of the attic in the big old house where I grew up, buried beneath fifty-five years of the flotsam and jetsam that our mother would not or could not throw away. Every report card, every cocktail napkin, every Christmas card ever received was there. A single ice-skate guard; broken reel-to-reel tape players; moldy sleeping bags; mess kits; stacks of vinyl records; Sears, Roebuck catalogs from the 1950s. On the very bottom of these strata was a squashed white gift box sealed with brittle yellowed tape.

Over the years, the attic’s contents had been dripped on from a leaking roof, gnawed on by mice, and sprinkled with acorns from squirrels that had somehow gained entry. Draped on top of everything were slabs of pink cotton candy–like insulation that had fallen down from between the rafters. I’d seen plenty of places like this while foraging at estate sales, but never so dense and familiar. Our mother had a certain sense of tidy order, but zero editing skills. She thought everything mattered or would eventually. Any organization she’d hoped to keep was destroyed by us kids regularly tossing it all like a salad when looking for something, or stuffing additional items in there for safekeeping. An undiscerning eye would have scanned the sodden pile and chucked the whole lot.

But while my mother was a natural hoarder, I am a natural scavenger.

Yard sales and dumps are my playground. Always sifting deeper than most, looking for treasure, I have no end of patience for going through piles of apparently worthless stuff. I am a connoisseur of junk, ever searching for the rare and precious. I see now that I was in training to find the most precious treasure of all.

There in the attic, as the archaeologist in me excavated below decades of family accumulation, I found the Lucy of Dad. The earliest inklings of who he was going to become. The first sparks that lit the dazzling Roman candle that was my father. Two hundred and twenty-six letters that he wrote to my mother from 1941, when he was just nineteen years old, to 1945, when he was twenty-four.

Some are typed, using the typewriter as an artistic tool the way a painter uses a brush, and some are handwritten and illustrated in pencil. His penmanship is remarkably legible, and as with the content of his novels, you never have to struggle to decipher what he is saying. These letters show that my father was well formed as a writer at a strikingly young age. He just lacked confidence, an audience, and experience. My mother became his confidante and audience before he dared to even refer to himself as a writer. The experience would come soon enough.

Kurt pursued Jane for four years with these astonishing letters. It is thrilling to read how in love with her he was. She was the single object of his desire. He half-heartedly dated other women and would say they had the right body but the wrong soul. My father’s intense love for my mother, expressed in his crystal-clear handwriting, is breathtaking—and also devastating, knowing what I know now: that he would stop loving her. Would Romeo have left Juliet eventually if they had lived long enough? How could a love so dazzling and singular and determined fizzle?

When I went up to the attic that day, I was not expecting to find more than some old bank statements. The discovery floored me figuratively and literally. I spent the next four hours with the box between my legs, reading letters written seventy-seven years ago. Knowing full well how it all turned out made for a powerful emotional cocktail. My heart broke for my mother and father. I don’t cry very often, but I had to be careful handling the fragile papers as tears slid down my cheeks.

* * *

—

This collection is a portrait of first love and early ambition, and what was found and born and lost between two brilliant young minds and hearts. If I had been my mother when he was leaving twenty-five years later, I would have dug out those letters and thrown them in his face, yelling “What about these!? See how relentlessly you pursued me? You vowed we’d grow old together, love each other forever, and do so much good in this life. What about those promises, you asshole?!!” But my mother wasn’t like that.

Their marriage did not survive, but the letters did. In my estimation they are among his finest writing, right up there with The Sirens of Titan, Cat’s Cradle, and Slaughterhouse-Five. They come from a time and place more passionate, pure, and inspired than any other in his life. He was not writing for fame or money, but to win the love of a woman.

Pre-1941: Two Indianapolis Families

Kurt’s parents were German American, secular humanists. His mother, Edith Lieber Vonnegut, was born to a wealthy beer-brewing family in Indianapolis. The brewery suffered a catastrophic downturn during Prohibition, and the Great Depression further eroded their fortune. Kurt’s father, Kurt Vonnegut, Sr., was the son of the first licensed architect in Indiana and an architect himself. Kurt junior was the youngest of three children, five years younger than his sister, Alice (Allie), and eight years younger than his brother, Bernard. He was the doted-upon baby of the family and enjoyed a loving, lively childhood.

Jane was from a Quaker family of Anglo-Irish descent. Her father, Thomas Harvey Cox, was an Indianapolis lawyer. Her mother, Riah Fagan Cox, held a master’s degree in classical literature; she coauthored a grammar textbook that would go on to become a standard in the field. She also taught at the Orchard School, the primary school that both Kurt and Jane attended. Up until Jane left for college, her life was dominated by the unpredictable health of her brother and mother. Riah was a brilliant scholar and teacher, but she suffered from episodes of mental collapse for which she was periodically institutionalized. Jane’s only sibling, Gussie, was mentally fragile as well, after a surgical accident severed a facial nerve, leaving his face slightly disfigured.

1941: First Love

Kurt and Jane attended school together from kindergarten through third grade at the Orchard School in Indianapolis, but they didn’t encounter each other again until they were nineteen, when they both attended a social at the local Woodstock Country Club on August 15, 1941. They discovered they shared a passion for social justice, an altruistic desire to contribute to the world, and a love for art in all its forms. They formed a deep bond that evening and spent almost every minute together for the next ten days, until he left for Cornell University and she for Swarthmore College for their sophomore years. This is when their correspondence began. (My mother’s nickname was Woofy, as you’ll see in the letters. I have no idea why. I don’t think she l

iked it, because it was never used after college, and when I asked, I never got a satisfying answer.)

Jane was an excellent student. Having always loved books, she majored in literature, with minors in philosophy and history. A former boyfriend once described her as an “extraordinarily cute, lovely young lady with a challenging intellect.”

Kurt, meanwhile, was not a good student. He was poorly matched to his major: chemistry. His father and brother felt strongly that science was the future and had urged young Kurt to study that field. In reality, he spent most of his time editing Cornell’s newspaper, The Daily Sun, and writing to Jane. He was almost singularly focused on her and became frustrated when she did not write more often. Jane, on the other hand, was enjoying a heavy course load and many suitors, as she was enchanting, beautiful, smart, and away from an unhappy home for the first time. Her freedom had just begun. She must have been hesitant to allow Kurt to tie her down so quickly, even though he was already asking her to marry him in his earliest writings to her. His devotion to her was unusual for the time; the norm in the 1940s was for young men and women to date a variety of people. I don’t think Jane was expecting Kurt to become so exclusively enamored with her after their summer romance. That they were in different states and different schools made total commitment extra-impractical.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked, leading President Franklin D. Roosevelt to ask Congress to declare war on Japan. America entered World War II.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

1942: Junior Year

In May 1942, Cornell informed Kurt that if there was no improvement in his grades, he would not be continuing at the university. He was failing biochemistry and organic chemistry and had been put on academic probation. Despite this, he ignored his junior year classes and channeled all his time into editing the Sun and writing to Jane. They continued to visit each other for parties and events at their respective campuses. (Most of the parties were at Cornell; Swarthmore was more of a buttoned-up institution.)

By December, Kurt was flunking out. He developed a mild pneumonia while home on Christmas break. Meanwhile, Jane was on course to having a stellar academic year, wholly focused on her studies. She didn’t correspond with Kurt as often as he would have liked. All the while, the shadow of the war was looming closer to their lives.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

1943: War at Home

In January 1943, Kurt decided not to go back to Cornell. Though he was deeply anti-war, he felt that World War II was one that had to be fought. He enlisted in the army rather than wait to be drafted, or expelled from Cornell. He was rejected once for his pneumonia but tried again, successfully this time, in March.

Kurt trained at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville and Fort Hayes in Columbus, Ohio. In June, he qualified for a program called the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which enabled him to study introductory mechanical engineering at the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh. In qualifying for this program, Kurt was under the impression that he would not be sent overseas to fight the war on the front lines, which was a great relief to his family.

* * *

—

September found him continuing furlough coursework at the University of Tennessee.

Jane was beginning her senior year. In addition to Kurt, she had several suitors with names like Bates and Kendall, but her academic life was more important to her than dating and letter writing. Kurt’s letters were outnumbering hers six to one. He would date other women from time to time, but that seemed more like a ploy to get Jane’s attention than anything else. He had time on his hands. She did not. In addition to the pressure of her studies, Jane was stressed about her mother, who had just suffered another mental collapse, which Jane did not think Riah would survive.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

1944: Shipping Out

By mid-April 1944, the ASTP program was canceled, as troops were needed for D-Day. Kurt was assigned to the 106th “Golden Lion” Infantry Division, 423rd Regiment, and ordered to Camp Atterbury in Indiana to train as an intelligence and reconnaissance scout, which involved interpreting maps and setting up advance observation posts.

On May 14, while Kurt was home on leave from Camp Atterbury, his mother, Edith, died of a barbiturate overdose. She was fifty-five. Edith was described as a very beautiful woman, tall and statuesque, stately and dignified in bearing but with a lively sense of humor and an easy laugh. Barbiturates were readily prescribed in the 1940s as a sleep aid and to treat anxiety, and unfortunately many patients became unwittingly addicted. In his grief, Kurt leaned on Jane, which brought them even closer.

In June, Jane graduated from Swarthmore with high honors and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. She was also awarded a prize for having the best personal library of any graduating student; she had an extensive collection of Russian literature, volumes of poetry, and all of Shakespeare’s works. In late summer, Jane moved to Washington, D.C., to begin a job as a clerk analyst in the counterintelligence branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor of the CIA. Jane did secretive work as a research assistant, specializing in the Far East while also studying Russian at George Washington University.

By September, Kurt was packing to go overseas with the rest of the 106th Division. Fifteen thousand soldiers were being sent to relieve the 2nd Division at the front in Belgium.

On October 17, Kurt set sail from Manhattan on the Queen Elizabeth and arrived in Cheltenham, England, two weeks later. On December 6, the 106th Division crossed the English Channel, waded ashore at Le Havre, France, and drove into Belgium. Ten days later, on December 16, Kurt’s division was swept into the Battle of the Bulge, during which he was taken prisoner of war along with 7,000 others and marched hundreds of miles into Germany. On December 21, Kurt’s family was notified that he was missing in action.

Click here to view this content as text.

Click here to view this content as text.

Slaughterhouse-Five

Slaughterhouse-Five Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction

Bagombo Snuff Box: Uncollected Short Fiction God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian

God Bless You, Dr. Kevorkian Breakfast of Champions

Breakfast of Champions While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction

While Mortals Sleep: Unpublished Short Fiction Slapstick or Lonesome No More!

Slapstick or Lonesome No More! Cat's Cradle

Cat's Cradle The Sirens of Titan

The Sirens of Titan A Man Without a Country

A Man Without a Country Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction

Look at the Birdie: Unpublished Short Fiction Bluebeard

Bluebeard Hocus Pocus

Hocus Pocus The Big Trip Up Yonder

The Big Trip Up Yonder Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage

Palm Sunday: An Autobiographical Collage Jailbird

Jailbird Happy Birthday, Wanda June

Happy Birthday, Wanda June Welcome to the Monkey House

Welcome to the Monkey House Player Piano

Player Piano Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage Love, Kurt

Love, Kurt Timequake

Timequake God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater

God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater 2 B R 0 2 B

2 B R 0 2 B The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity

The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity Mother Night

Mother Night Deadeye Dick

Deadeye Dick Galápagos

Galápagos Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday We Are What We Pretend to Be

We Are What We Pretend to Be Look at the Birdie

Look at the Birdie Basic Training

Basic Training Armageddon in Retrospect

Armageddon in Retrospect Basic Training (Kindle Single)

Basic Training (Kindle Single) If This Isn't Nice, What Is?

If This Isn't Nice, What Is? Bagombo Snuff Box

Bagombo Snuff Box The Petrified Ants

The Petrified Ants Cat's Cradle: A Novel

Cat's Cradle: A Novel Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)

Fates Worse Than Death: An Autobiographical Collage (Kurt Vonnegut Series)